A legislative committee has agreed to draft a bill that would provide $105 million to local governments for the next biennium, the same amount they received in a special appropriation from the state two years ago.

How that request will be received by a Legislature that needs to find about $250 million a year to make up a budget shortfall for education, though, is anyone’s guess. There are plenty of hurdles for local governments to clear before they receive an extra dime, including an inevitable grilling from the Joint Appropriations Committee to justify the additional funds.

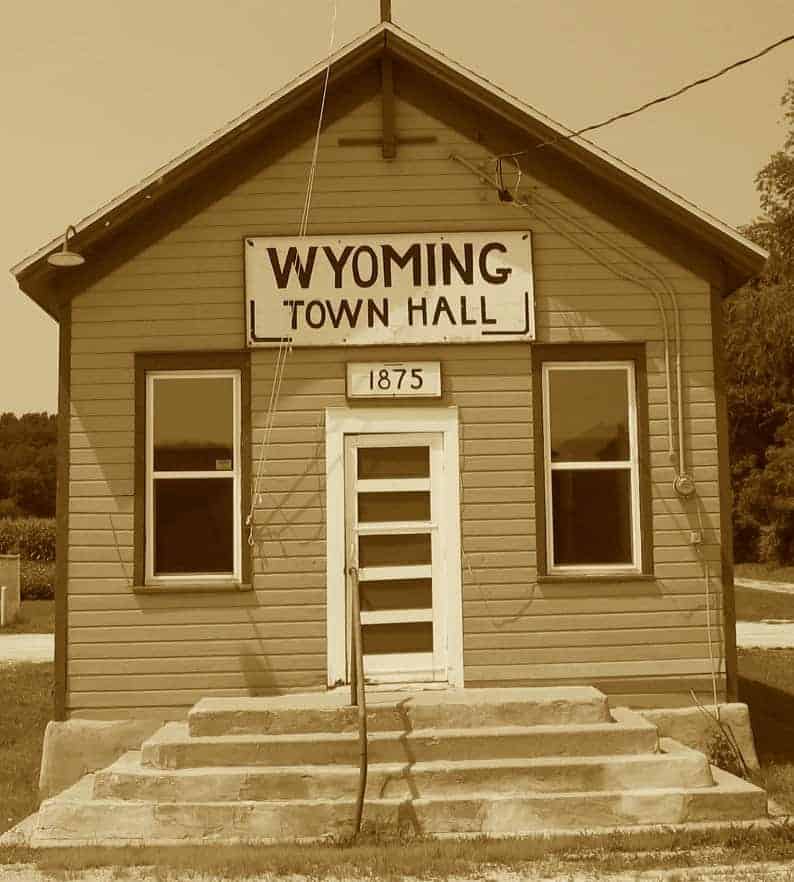

Groups representing cities, towns and counties presented a united front to the Joint Revenue Interim Committee when it met recently in Buffalo. The Wyoming Association of Municipalities (WAM) and the Wyoming County Commissioners Association (WCCA) said they have a critical need for a continued appropriation that the state gave them in the last biennium.

Those funds were taken out of state budget reserves, which some lawmakers have developed a renewed reluctance to tap until the education funding crisis is solved.

Which communities have the hardest of the hardship?

The $105 million for Fiscal Years 2016-17 was about half of what the Legislature gave cities, towns and counties the previous biennium, 2014-15, when the state was still flush from the most recent energy boom.

“We’re not asking for any more than we received [two years ago],” said WAM Executive Director Rick Kaysen, a former Cheyenne mayor. He said the $105 million is needed for FY 2018-19 to serve as a “bridge” for local governments while they address how they will generate local funds in the future so they can stop begging the state for money.

He said if cities, towns and counties are given permission by the state to raise their own revenues through taxes for general operations, only about 10 to 15 of the smallest communities would need to continue getting a special appropriation from the state. Sen. Dave Kinskey (R-Sheridan) told WAM, “The first step is for you to agree who the true hardship communities are and give us a list.”

Kinskey then proceeded to lecture the group, with more than a little snarkiness: “WAM’s never been able to give us that list because the minute one town starts to see another town getting something—all of the sudden something is off,” he said. “To cut the grand bargain you have to say, ‘Here are the small towns and how we provide for them.’”

The Revenue Committee that won’t raise revenues

Much of the decision whether to help local governments with their operating expenses rests on whether the Revenue Committee actually comes up with any revenue-generating bills to help fund education (or anything else). So far Republican legislative leaders vow to significantly cut funds for public schools before any tax hikes at all are even considered, and the Revenue Committee hasn’t identified any tax increases or new taxes that the Legislature is likely to approve.

Last year the Legislature considered a small hike on cigarettes taxes that would go toward education but it was ultimately rejected. The committee has already said no to even bringing up making smokes more expensive in 2018.

Tax increases on beer, wine and distilled spirits are the subject of a proposed bill being drafted by the panel, but it would raise only a tiny fraction of what is needed to keep education spending at its current level. There is no apparent legislative support at all for creating a state personal or corporate income tax or increasing property taxes or mineral severance taxes.

The committee did agree to draft a bill that would allow the state’s tourism industry to implement a special tax to fund the state tourism agency’s budget itself, which would free up about $25 million for other purposes.

“We’re about as low on staff as we can get and still keep the town running”

While it is also unpopular, the most likely tax idea to be debated by the full Legislature is a 1-cent increase in the state’s 4-cent sales tax. The regressive tax hike is estimated to bring in an additional $157 million to the state, of which $32 million for cities and $17 million for counties would be available under the state’s current formula for distributing sales tax funds.

Without the additional state funding, small city governments say they will have trouble operating. Dayton Mayor Norm Anderson said, “We’re about as low on staff as we can possibly get and still keep the town running.”

Clearmont Mayor Chris Schock said his town of about 150 people also depends on the state’s money. Without it, he said, the town would be forced to either lay-off employees or cut their hours. Meanwhile, Ranchester Mayor Peter Clark said his town relies on state funding for about 95 percent of its budget.

Cities, towns and counties have never recovered since the Legislature eliminated the sales tax on groceries in 2006. State lawmakers promised to make local governments whole again due to the expected significant declines in their sales tax revenues, but they only provided additional money for the next year before telling local officials they had to go it alone without state help.

Food tax foolishness

While there have been sporadic special allocations in the past decade for cities, towns and counties, the entities still lack a consistent source to make up for lower sales tax revenue on food. Earlier this year some legislators suggested bringing back the food tax, but that idea isn’t realistic and no one is pushing it. The GOP leadership is far from the sharpest tool in the shed, but it’s smart enough to know that once you give people a tax break for more than a decade, you can’t reinstate it without pissing off a lot of voters—especially if it’s something that’s going to affect working people most.

WAM, which represents 99 cities and towns, said it wants the ability to pass a local option sales tax without the county or other cities allowed to vote on it.

Kaysen said Wyoming cities generally have good relationships with most counties, but currently a county could prevent a city from putting a local option sales tax on the ballot—even though that’s never happened.

Peter Obermueller, WCCA executive director, said county commissioners should continue to have a say in that decision because county residents shop in cities but would no longer have a say on such tax issues.

Both organizations said if the Legislature ultimately turns to a sales tax increase to help fund education, they would like lawmakers to make permanent a “fifth penny” general option tax aimed at helping local governments. The committee, though, defeated that idea by a 2 to 9 vote.

Sign up for Better Wyoming emails on our homepage, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.