In the first of a three-part series on barriers to opportunity that young people and families face in our state, Better Wyoming looks at the Legislature’s recent efforts—and failures—to address the growing problem of mental illness among Wyoming K-12 students.

+

The Wyoming Constitution requires the state to provide quality public education to all Wyoming children.

After all, an educated workforce is the foundation of a strong economy, and education is often a big factor in an individual’s ability to lead a good life.

People often debate what, exactly, qualifies as a “quality education.” But we can all agree on a few things.

For instance: A student cannot learn much if they are suicidal, depressed, or suffering from unchecked mental illness.

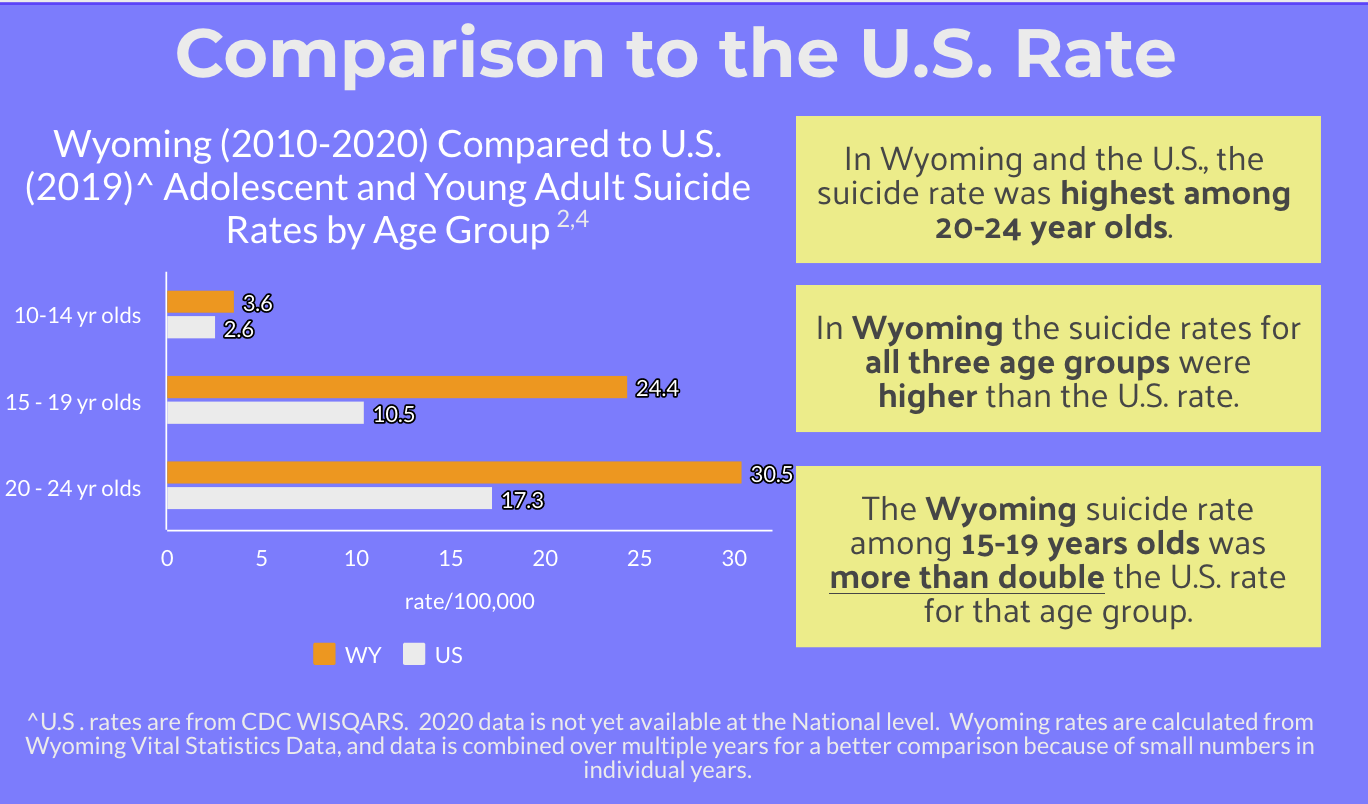

Wyoming has long been among the worst in the nation when it comes to suicide rates, including among student-age kids. This is just part of the state’s ongoing mental health crisis.

Recently, the problem has become even worse.

That’s why the Wyoming Legislature’s Management Council assigned the issue of K-12 mental health to the Legislature’s Joint Education Committee. The committee met recently in Casper to discuss what, if anything, state lawmakers might do about the problem.

Blocking help

During its 2023 session, the Wyoming Legislature voted down a bill that would have offered school districts funding to provide better mental health treatment for students.

House Bill 34, “School Finance – Mental Health Services” passed the House, despite the so-called Freedom Caucus voting in a bloc against it.

But on the Senate Education Committee, Freedom Caucus members control three of the five seats. The committee voted down HB-34 along those lines.

Sen. Bo Biteman (R-Ranchester), a Freedom Caucus member on the Senate Education committee, argued that churches—not schools—should provide kids mental health treatment.

Two of his colleagues, Evie Brennan (R-Cheyenne) and Cheri Steinmetz (R-Lingle), agreed.

Now, faced with the same political makeup and legislative obstacles in 2024, lawmakers intent on improving mental health services for Wyoming youth will have to look for new paths forward.

Suicide epidemic

Roughly one out of every 10 students in Wyoming has attempted suicide in the past year, according to the state Department of Health’s “Prevention Needs Assessment Survey.”

Nearly 20 percent of K-12 students have considered the act. In Wyoming, suicide is the second leading cause of death for people 10 – 24 years old.

Of course, suicide is at the extreme end of the spectrum of mental health challenges. More Wyoming students struggle with issues like depression or bipolar disorder, which are perhaps less urgent but can be dramatically harmful to a young person’s life—and their learning.

According to Jen Davis, a senior health policy advisor for Governor Mark Gordon, students facing these challenges in Wyoming are often without any help or access to treatment.

For instance, Davis told the Joint Education Committee, about half of young people in the state diagnosed with major depression do not receive any mental health treatment at all.

Scarce services

Public schools have proven to be a successful point of access to mental healthcare for children who may be otherwise unable to get the services they need.

Even where school counselors do exist, they are often pulled to other tasks, like monitoring standardized tests.

But only when schools can provide the help.

Mental health resources in Wyoming schools exist in a patchwork across the state. They are available to students on a case-by-case basis, depending on a number of factors—including whether an individual school or district has managed to retain a qualified mental health professional.

Statewide, rural schools are far less likely to provide mental health services, just as rural communities are less likely to offer mental healthcare services in general. In turn, some of the most dire impacts of mental illness in Wyoming affect people in rural areas.

Kayla Wilkinson, president of the Wyoming Counseling Association, told the Joint Education Committee that even where school counselors do exist, they are often pulled to other tasks, like monitoring standardized tests. This makes it more difficult to perform their core task of caring for students.

Tate Mullen, of the Wyoming Education Association, noted that the Legislature’s chronic underfunding of school districts makes the problem more difficult to manage, as does the state’s ongoing teacher shortage, which spreads staff thin in schools throughout the state.

Parental rights

During the Legislature’s most recent session, earlier this year, lawmakers attempted to direct more resources to school districts specifically for hiring more counselors and better mental health services for students.

HB-34 would have created a pool of funding that Wyoming’s 48 school districts could apply for, up to $120,000 per district. The bill proposed to set aside $11.5 million in state funding for two years, in addition to available federal funds.

Sen. Biteman, on the Senate Education Committee, led the attack against HB-34 during the 2023 session. He argued that providing mental health services is beyond the scope of what public schools should do, and that increasing the availability of mental health treatment to young people could encroach on parental rights.

Churches and families alone should be responsible for a young person’s mental health, Biteman said.

Biteman also argued that, since HB-34 only provided funding for a two-year period, districts would likely hire more mental health providers only to have the funding run out.

Notably, the supplemental state budget that the Wyoming Legislature passed in 2023 included putting $383 million into savings. That amount alone could have funded the proposed K-12 mental health program for several decades.

Struggling children, struggling state

In her comments at the recent Joint Education Committee meeting in Casper, Davis, the governor’s policy advisor, spoke to some of these concerns, and argued that the state indeed should play a role in addressing student mental illness.

“When we see a child in crisis or struggling, that means there’s a family struggling,” Davis said. “If there’s a family struggling, that means their business is struggling. If a business is struggling, that means our community is struggling. If our community is struggling, that means our state is struggling, which is why we’re all here.”

The Joint Education Committee did not take action on K-12 mental health at its recent meeting. But members indicated that they would continue the discussion and potentially draft new legislation at the committee’s next meeting in Cheyenne in August to propose for the Legislature’s 2024 session.