[one_third last=”yes” spacing=”yes” center_content=”no” hide_on_mobile=”no” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” background_position=”left top” border_position=”all” border_size=”0px” border_color=”” border_style=”” padding=”” margin_top=”” margin_bottom=”” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”” animation_speed=”0.1″ class=”” id=””][fusion_text]May 3, 2017

Imagine you’re sitting in prison, convicted of a crime you did not commit. One day, three years into your 20-year sentence, your lawyer visits and tells you that new evidence has come to light that proves your innocence.

In most states, that would mean you’d be headed home soon to rebuild your life. But in Wyoming, it wouldn’t matter—unless new non-DNA evidence is presented within the first two years of a person’s sentence, it’s null and void.[/fusion_text][/one_third][three_fourth last=”yes” spacing=”yes” center_content=”no” hide_on_mobile=”no” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” background_position=”left top” border_position=”all” border_size=”0px” border_color=”” border_style=”” padding=”” margin_top=”” margin_bottom=”” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”” animation_speed=”0.1″ class=”” id=””][fusion_text]You might be innocent beyond a doubt. But under Wyoming law you’re going to remain in prison to rot.

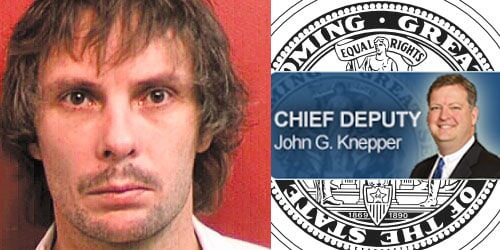

An “actual innocence” bill to end this terrible injustice won unanimous approval in the 60-member Wyoming House in February. But when it came to the Senate Judiciary Committee, the proposal hit a roadblock in the form of Chief Deputy Attorney General John G. Knepper. He waited until the panel’s final meeting of the session to warn the five senators about the legal chaos he’s convinced would ensue if the bill passed, like inmates clogging the courts with frivolous attempts to file for new trials based on nothing.

Knepper convinced the Senate committee to sit on the bill and ask the Legislative Management Council for permission to study the issue for the second year in a row.

Late last month, it looked like Knepper might stop the bill again as the Joint Judiciary Committee considered it during a meeting in Thermopolis. But thanks in large part to testimony from Michelle Feldman, a state policy advocate of the Innocence Project in New York, legislators now seem to understand that none of the grave scenarios Knepper outlined was likely to happen.

Feldman said 2,018 convictions have been overturned in the United States since 1989, and 83 percent of them used non-DNA evidence. There is no time limit in any state for DNA evidence to be used to exonerate a wrongly convicted inmate, but Wyoming is one of only two states that have a two-year time limit to introduce new non-DNA evidence and petition for a new trial.

How can an actual innocence bill impact someone previously found guilty of a crime in Wyoming? Feldman told the committee about Troy Willoughby, who was convicted in January 2010 for the cold-case murder of a woman south of Jackson in 1984.

Feldman said law enforcement interrogated Willoughby for 17 hours over two days, resulting in a false confession he later recanted. It took a jury only an hour to find Willoughby guilty of first-degree murder and he was sentenced to life in prison.

But in June 2011—ironically, two days after the Wyoming Supreme Court upheld his conviction—Willoughby’s attorneys were provided evidence that Sublette County officials withheld from the defense. At the time of the murder, their client was being questioned by an officer about a rock-throwing incident 65 miles away, so he couldn’t be the killer. After being awarded a new trial, he was acquitted.

Feldman explained that under current Wyoming law, the two-year time limit to introduce new non-DNA evidence is absolute. Willoughby was lucky that evidence was turned over about 18 months after his conviction. If it had been two years and a day, Feldman said, he would not have received a new trial and would still be serving a life sentence.

Maybe the governor could have commuted his sentence, but in tough-on-crime Wyoming, there is immense political pressure—from people like Knepper—to ignore the truth and let folks hang.

Freeman said despite Knepper’s fear that hundreds of inmates will file for new trials, the actual numbers in states that have passed similar bills have been small. Utah has only had eight filed since 2008.

At the February Senate Judiciary meeting where the bill stalled, DeWayne Spellers of Wyoming testified that he has been trying to clear his name after a felony conviction for filing a fraudulent insurance claim from a traffic accident that authorities said he caused. He was given probation, but 16 years later an FBI agent informed him that another man confessed to causing the accident.

Spellers said he has been unable to receive a new trial under Wyoming law. Sen. Liisa Anselmi-Denton (D-Rock Springs) said there should be a mechanism for Spellers to be cleared.

“These people don’t want to go through hoops to have their records expunged,” she told Knepper. “They want to vote and be able to own a gun in Wyoming—so why are we torturing them?”

Sen. Dave Kinskey (R-Sheridan) said he had been prepared to approve the actual innocence bill during the session because it had been thoroughly vetted, but he agreed to wait because he expected Knepper “to bring us some very specific things so we could all be on board with [the bill].” Obviously underwhelmed by the deputy AG’s presentation in Thermopolis, the committee told Knepper to bring any amendments he suggests to the committee’s next meeting in June, so the overwhelmingly popular bill can move forward with plenty of time to be discussed during the session.[/fusion_text][/three_fourth]