An unlikely coalition of young conservatives, long-serving moderates, and progressives banded together in 2019 to try to end the state of Wyoming’s ability to execute even its worst criminals.

That the group nearly succeeded in abolishing Wyoming’s death penalty seemed to surprise … well, pretty much everyone. But maybe it shouldn’t have.

“The effort to repeal the death penalty was so strong and got as far as it did because it brought together advocates who argued from diverse perspectives—spiritual, practical, compassionate, fearful of a flawed justice system, and responsible governance,” said Marguerite Herman, a League of Women Voters lobbyist and longtime presence at the Legislature.

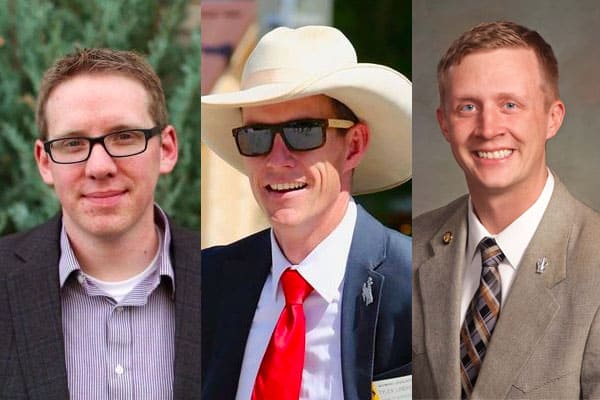

House Bill 145, sponsored by Rep. Jared Olsen (R-Cheyenne), won House approval by a 36 – 21 vote and had the unanimous support of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

A day before its final vote in the Senate, the bill’s backers thought they had the 16 votes necessary to succeed. But when the time came, the bill failed, 12 – 18.

Nevertheless, it was by far the most successful attempt ever to repeal Wyoming’s death penalty.

A very expensive bargaining chip

As Herman explained, lawmakers presented many arguments against keeping capital punishment in Wyoming. But HB-145’s backers returned to one argument again and again: cost.

Wyoming hasn’t executed anyone since 1992, when convicted murderer Mark Hopkinson died by lethal injection. But the state still spends in the ballpark of $1 million a year as the result of capital punishment remaining part of our laws.

“As long as prosecutors have the death penalty in their tool box they’re going to use it.”

Wyoming State Public Defender Diane Lozano explained to several Legislative committees that prosecutors use the threat of a death sentence as a negotiating tool as they pursue cases.

“As long as prosecutors have the death penalty in their tool box they’re going to use it, whether it’s as a bargaining chip or otherwise,” Lozano said.

But any time a prosecutor invokes the possibility that he or she will pursue a death sentence, extra costs are involved. These costs, which are the result of constitutional protections, are borne by public defenders’ offices, the Department of Corrections, district attorneys, and—of course—all paid for with public money.

Lozano said her office “lives in abject fear” that it will get more than one death penalty case per year because of the strain it puts on her agency’s budget. The cases require her, for instance, to hire extra private investigators and mitigation specialists “to investigate back three generations to get the client’s life story,” she said.

Every two years, Lozano said at least two members of her staff must receive the latest training on how to defend a capital murder charge.

All of these requirements are in place to ensure the death penalty is applied in only the most extreme—and certain—instances.

The last person on Wyoming’s death row was murderer Dale Eaton, who had his death sentence overturned. Lozano’s office spent $145,000 on the original case and has been ordered by a federal court to spend $2.1 million on Eaton’s resentencing.

High cost, no deterrent

The public defender’s office isn’t the only one that shoulders extra costs during capital cases.

State Department of Corrections Director Bob Lampert said housing an inmate facing death costs about 30 percent more than a normal prisoner.

“None of them ever told me that they stopped to consider whether the crime they were about to commit could get them the death penalty.”

Lampert said execution costs have also increased significantly because pharmaceutical companies no longer make the chemicals that Wyoming law requires.

Lampert worked for the Texas Department of Corrections and participated in 37 executions over seven years. He said the high cost wasn’t the only reason he supported getting rid of capital punishment in Wyoming.

“I had the sobering experience of getting to know the death row inmates,” Lampert said. “I can tell you that nothing can prepare you for the obligations that come with the job.”

He does not view capital punishment as a deterrent to violent crime, either. Lampert said he spent the final hours with several inmates leading up to their executions. “None of them ever told me that they stopped to consider whether or not the crime they were about to commit could get them the death penalty,” he said.

Gut check

Olsen, the bill’s sponsor, told members of the House during debate that when he sought co-sponsors for his proposal, several lawmakers asked him: What if the murder victim was a member of his family?

“We call ourselves a civilized nation, and we’re still killing our own people. I just don’t understand it.”

“My gut actually said, ‘Yeah, I would want that person put to death,’” Olsen said. “But you know what? That’s what’s wrong with the system. My gut is wrong. It’s not based on reason.

“Ask yourself if it’s reason, or it’s blind [justice], or if it’s nothing but fear and anger,” he said.

Since the death penalty was reinstated federally in 1973, 156 death row inmates have been exonerated nationally. One of them, Gary Drinkard, served on Alabama’s death row for six years. He came to Wyoming to speak in favor of Olsen’s repeal bill.

“Innocent people have been killed,” Drinkard told the Senate Judiciary Committee. “We call ourselves a civilized nation, and we’re still killing our own people. I just don’t understand it.”

For these and other reasons, many states of all political stripes are considering repealing their death penalties. Twenty states have already ended capital punishment.

Incoherent rambling wins the day … for now

But in the far-right Wyoming Senate, where reason seldom holds sway, not even fiscal conservativism was enough to persuade lawmakers to pass the abolition bill.

The current crop of Wyoming State Senators is prone to some pretty far-out arguments. But debate over the death penalty bill elicited some exceptional remarks.

The religious views of Sen. Lynn Hutchings (R-Cheyenne) quickly went viral on Twitter and were picked up by national press. She argued that without capital punishment, Jesus Christ would not have been able to die to absolve the sins of mankind.

“Governments were instituted to execute justice,” Hutchings said. “If it wasn’t for Jesus dying via the death penalty, we would all have no hope.”

Sen. Anthony Bouchard (R-Cheyenne) said having the death penalty keeps Wyoming’s justice system from turning into the type seen in other states, like California. He weirdly noted that California has allowed some inmates to undergo gender reassignment surgery.

“I think we’re becoming a lot like other states, and we have something to defend,” Bouchard said. He neglected to mention that California still had the death penalty at that time (California Governor Gavin Newsome issued a blanket stay of executions earlier this week).

But the lunatics won’t run the asylum forever. Bipartisan support for ending the death penalty is growing nationwide, simply because it seems less and less worth keeping around.

Herman, from the League of Women Voters, said the issue will return to the Wyoming Legislature.

“I believe that awareness created by the 2019 debate will result in more individuals and groups telling their elected representatives that Wyoming does not need the death penalty to deter crime,” she said. “That we don’t want to keep a costly and ineffective law on the books, and that they don’t want their government to be the agent of their desire for vengeance.”