When most of us think about government response to climate change, it’s usually on a global scale—things like the Paris Climate Accord or the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

But scores of decisions are made by state, county, and city governments that have climate-related impacts, too.

Local officials have the ability, for instance, to help reduce carbon emissions, support renewable energy, and protect natural resources that are threatened by the climate crisis.

Of course, the Wyoming Legislature plays a big role in propping up the state’s fossil fuel industries—protecting oil, gas, and coal companies even as the earth heats up.

In addition, people sitting on city councils and county commissions have the ability to make or break climate-friendly projects.

As the Nov. 8 general election approaches, voters throughout Wyoming have important choices to make for races like city council, county commission, and school board, and there remain more than a dozen closely contested legislative races.

There are many issues to consider going to the polls to vote for local government this fall. Climate should be one of them.

Carbon neutral city council

Ed Koncel, of Laramie’s Alliance for Renewable Energy (ARE), has seen firsthand how changes in city government can provide positive climate impacts.

As recently as a few years ago, Koncel said the Laramie City Council was not receptive to anything involving renewable energy.

Now, however, thanks to some turnover on council and some local organizing, things have changed.

“Our current council is absolutely fantastic,” he told Better Wyoming.

Thanks to advocacy from ARE, Laramie’s City Council passed a resolution in 2020 to make the city carbon-neutral by 2050.

Prior to that, organizers convinced councilors to join Local Governments for Sustainability, a global network of more than 2,500 local and regional governments committed to sustainable urban development.

Koncel said a turning point in ARE’s work to influence city council came when they revealed to councilors that Rocky Mountain Power had made available $500,000 in grant funding for renewable energy projects, and not a single entity from Wyoming applied.

“That really sparked their interest,” Koncel said. In April 2020, Laramie requested $120,000 for a grant to install solar panels on both the Community Recreation Center and the Laramie Ice and Events Center.

Aqua-conscious county commission

Advocates for clean drinking water in Albany County have likewise seen the difference between a county commission that’s hostile to their work and one that’s friendly to it.

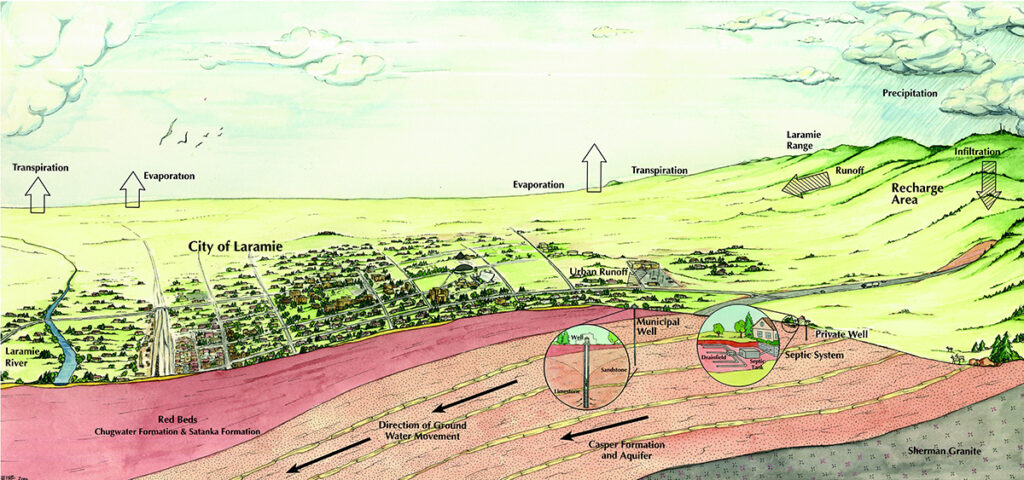

Laramie sits next to the aquifer that supplies about half of its drinking water. In fact, parts of Laramie are beginning to be built on top of the aquifer, which worries folks concerned about water quality.

Conor Mullen, an organizer with the Sierra Club – Wyoming, has helped push back against development on top of the aquifer, even as county commissioners have sometimes sided with residents who believe clean water is less of a priority than private profits.

“For some folks, protecting private property rights trumps protecting communal natural resources like aquifers,” Mullen explained.

But since the 2020 elections, the majority of Albany County Commissioners have agreed to help protect the aquifer, as climate-fueled drought continues to threaten water resources across the West.

The county now has a robust plan to protect its drinking water, and voters will decide this fall from a slate of candidates who have very different positions when it comes to ensuring that Laramie has water to drink.

Renewable energy: Site it right

County commissioners also have tremendous influence over renewable energy development—for better or for worse.

In Sweetwater County, commissioners approved in 2018 a solar farm that blocked a pronghorn migration route. This caused locals to denounce the farm and, more generally, solar energy development.

Ill-devised projects like this do more to hurt the movement against climate change than help it, simply because of the real harm they do to wildlife and the bad PR they create.

On the other hand, commissioners in Albany County saw past a small group of loud landowners trying to block a wind farm in 2020. They unanimously approved the Rail Tie wind project, which will power 180,000 homes once it’s complete.

Rail Tie developers spent nearly two years studying how wildlife is using the area, existing habitat, and any migration corridors or flight paths.

Mullen said the Sierra Club ultimately backed the project, since it used land that was already mostly developed and, by and large, mitigated human and wildlife impact.

“Climate change is here, the planet is warming and we have immense issues we’ve got to tackle,” Mullen said. “We need to find solutions quickly. On the other hand, renewables are not perfect, and they can’t just be implemented and sited without regard to a surrounding community, environment or ecosystem.”

Climate change will not be solved in one fell swoop, even by bodies like the United Nations. Instead, it will be a process largely accomplished by individual projects overseen by local elected officials.

When Wyoming goes to the polls this fall, voters should keep in mind that much of the fight against climate change will be decided in the realm of city, county, and state governments.