Wyoming lawmakers love a good “boom” for the oil, gas, and coal industries, like the recent one we’ve had as a result of high gas prices.

For one thing, a “boom” means high-paying jobs will stick around in these industries for a little bit longer.

But mostly, lawmakers love that they can continue to shake their fists at the prospect of higher taxes—always a politically popular thing to do—even while they remain able to fund public services like education, healthcare, and roads (also popular).

That’s because more than half of Wyoming’s total state budget comes from taxing the fossil fuel industries.

But for every boom, of course, there’s a bust. That’s when we experience the flipside: mass layoffs, cuts to school and healthcare funding, an inability to hire snow plow drivers, etc.

Anyone who’s lived in Wyoming for any stretch of time is familiar with our busts. Most people are sick of them.

Politicians have talked for decades about how to end Wyoming’s boom-and-bust cycle. Sure, we need to diversify our economy beyond the oil, gas, and coal industries.

But we also need to diversify our tax structure.

A person who buys a cup of coffee for $4 generates more tax revenue than a tech tycoon who buys a $40 million mansion.

Growing new industries outside of the fossil fuels sector actually costs Wyoming more money than it generates, since we have no real way to tax non-fossil fuel industries to support their development.

Of course, average Wyoming residents are feeling the squeeze of inflation and higher property taxes already. So generating additional revenue from raising taxes on the middle class is a political non-starter.

Luckily, Wyoming has an ace in the hole: A little ol’ place called Teton County, where some of the richest people in the world “live.”

There, for instance, because Wyoming has no real estate transfer tax, a person who buys a cup of coffee for $4 generates more tax revenue than a tech tycoon who buys a $40 million mansion.

According to a new report by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), Wyoming has several options to generate new tax revenue from our ultra-wealthy residents and decrease the state’s reliance on boom-and-bust fossil fuels—even while keeping taxes low on the middle class.

All we need to do is tax Jackson.

A “wealth tax” for households with more than $30 million

According to ITEP, Wyoming is one of 14 states that are home to an above-average concentration of extreme wealth—a small group of people with unbelievable amounts of money.

The nonprofit, nonpartisan group describes several options for legislatures in these states—including Wyoming—to generate tax revenue by closing loopholes, taxing “non-labor” investment income, and shoring up tax shelters for folks who park their money here but reside elsewhere.

Each dollar of revenue raised by taxing Teton County’s ultra rich is one less dollar we’ll depend on from the boom-and-bust fossil fuel industries.

Teton County had the highest per capita income of any county in the nation in 2021 — $318,297. Even though that amount is far more than most Wyomingites could dream of earning in a year, the figure obscures the sheer amount of wealth hoarded at the base of America’s favorite mountain range.

According to ITEP, a small group of ultra-wealthy people in Wyoming—folks with fortunes worth more than $30 million—own nearly $187 billion worth of assets.

A net-worth tax—or “wealth tax”—applied only to households with more than $30 million could generate significant amounts of revenue, meaningfully broadening the state’s tax base.

For instance, a 2 percent wealth tax would bring in $2.4 billion a year, while a 5 percent rate would bring in nearly $6 billion—even exempting households worth less than $30 million.

In comparison, even though 2022 was a banner year for sales tax in Wyoming, the state only generated $1 billion in sales tax revenue.

Even if Wyoming were squeamish about squeezing people with just $30 million, a 2 percent wealth tax applied only to literal billionaires would generate $900 million, and would only affect 0.0017% of Wyoming taxpayers.

Wyoming’s newest billion-dollar industry

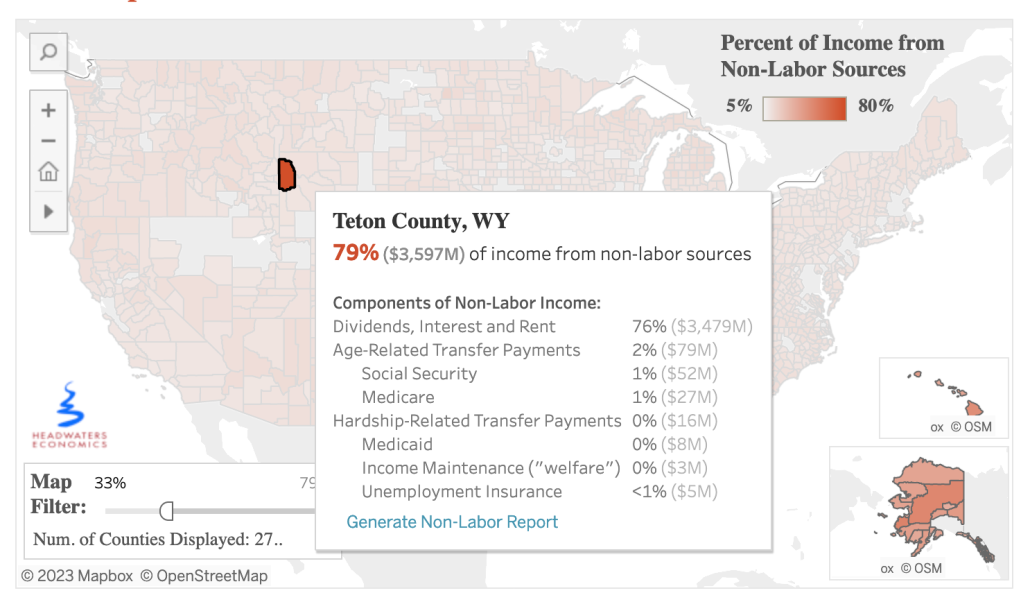

A report by Montana-based Headwaters Economics found that nearly 80 percent of Teton County residents’ personal income was “non-labor” income—money that came from investments, like the stock market, and not, you know, actually working.

While many Wyoming residents work hard and still struggle financially to get by, Teton County’s elite get to sit back and just watch the money pour into their bank accounts.

“Jackson’s economy is dominated by wealthy ‘amenity migrants’ and second home buyers,” the Headwaters report noted.

What do these folks all tend to buy? Luxury homes.

Justin Farrell, a Yale professor who was born and raised in Casper and is the author of Billionaire Wilderness, focuses his academic studies on Teton County’s ultra-wealthy. He often wonders aloud why Wyoming is willing to tax its traditional billion-dollar industries like oil, gas, and coal, but is unwilling to tax the state’s newest billion-dollar industry: luxury real estate.

According to the Jackson Hole Real Estate Report, the total dollar volume of real estate sales in 2021 was nearly $3 billion. Because Wyoming has no real estate transfer tax, none of those sales generated revenue for the state.

ITEP agrees in its report on taxing the ultra wealthy that states should look to luxury real estate for ways to generate revenue, as well as closing loopholes in estate and inheritance taxes among the super rich.

Taxes are never a cakewalk

For now, the conversation about diversifying Wyoming’s tax base is hypothetical—thanks to the current oil and gas boom, the state is sitting on a nearly $3 billion budget surplus.

But this upward blip starkly contrasts the overall trajectory of fossil fuel revenues, which have been steadily declining for a decade and by all measures will continue to do so.

The state’s Consensus Revenue Estimating Group—a team of economists that forecasts Wyoming’s fiscal fortunes—has warned lawmakers that a single bust could wipe out any short-term gains from a fossil fuel boom.

Any kind of new tax will cause an uproar in Wyoming, even if that tax only affects the super rich.

A single bust could wipe out any short-term gains from a fossil fuel boom.

We should recall, however, that creating Wyoming’s current tax structure was no political walk in the park.

When the Wyoming Legislature adopted the state’s first severance tax in 1969, the oil and gas industries, anti-tax lawmakers, and a good portion of the general public howled in objection.

But for the past 50 years, it has provided Wyoming residents with top-quality schools and other public amenities while keeping tax rates for individuals and other businesses among the lowest in the nation.

We have weathered a half-century of booms and busts from our fossil-fuel based economy, and now even that’s on its way out.

As Wyoming looks for ways to replace the revenue generated by these industries, we should look first to our very vastly wealthy neighbors in the northwest.