One of the main reasons Wyomingites oppose a state income tax is the long-held belief that average folks would have to pay much more of their hard-earned money to the government.

Boooo! Right?

But buried in the appendixes to a 20-year-old study of Wyoming’s tax structure, a different truth emerges: An income tax, under guidance from a 1974 State Constitutional amendment, would result in middle- and low-income earners in Wyoming paying little or no state income tax whatsoever.

The vast majority of new revenues from an income tax would come from citizens at the top of Wyoming’s income scale, who currently pay the lowest tax rate in the nation.

And those new revenues would be significant.

An obscure amendment provides Wyoming tax fairness

If Wyoming wants to makes its tax structure more equitable—and raise new revenues to offset its budget crisis—it should pass a state income tax.

That was the conclusion of the Tax Reform 2000 Committee appointed in 1998 by then-Gov. Jim Geringer, a Republican, after several years of sharply falling mineral severance tax revenues.

The TR2K committee was the last time Wyoming lawmakers took a serious look at tax reform. Its dozen members included business leaders and legislators who spent two years studying the state’s tax structure to determine the best ways to bring more revenue to state government.

In spite of the public’s well-known disdain for considering any new taxes, the panel’s top recommendation was adopting both a state corporate and individual income tax.

The committee emphasized the importance of an obscure yet important 1974 Wyoming State Constitutional provision, which declares:

In the event of a legislature ever implementing an income tax, the people of Wyoming will receive credits against that income tax for the sales, use, and property taxes they paid that year (see Article 15, Section 18).

It’s a populist safeguard against double taxation, designed specifically to ensure an income tax would affect the wealthiest among us most.

“An income tax that includes this provision makes the Wyoming tax structure more balanced and equitable,” the TR2K’s final report stated. “Higher incomes would pay a greater portion of the tax, but when all taxes households pay are considered, each level of income would pay approximately the same percentage in state taxes.”

In other words, unlike our current tax structure—under which the richest Wyomingites pay a roughly 1.2 percent tax rate while the lowest earners pay roughly 8.2 percent—an income-based tax with Wyoming’s unique constitutional provision would prompt the wealthy to finally pay their fair share.

“People should get credit for what they already paid before they pay more.”

What is this constitutional tax credit provision, and why don’t more people know about it? The answer to the latter question is simple: Since the state has never imposed an income tax, the tax credit system has never been used.

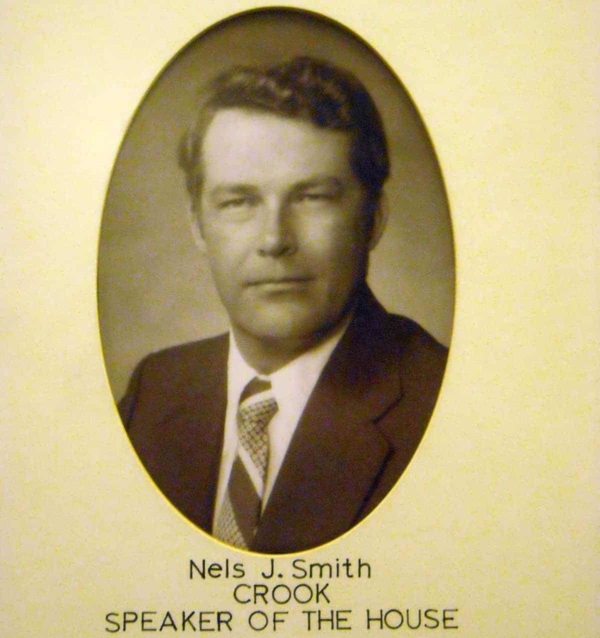

Former House Speaker Nels J. Smith (R-Sundance) proposed the tax credit amendment in 1973. Two-thirds of both the House and Senate backed it during that legislative session and voters overwhelmingly approved it a year later at the ballot.

Several Wyoming news articles following the amendment’s passage stated that Smith’s intention was to make sure the state never had either an individual or corporate income tax. But we talked to Smith, who’s now 78 and lives on his ranch near Sundance, to get the real scoop.

“That’s what some people said would happen,” Smith explained in an interview with Better Wyoming. “But my intent was if we ever had an income tax that people would get credit for the sales, use and property taxes they already paid.”

Smith said he believed that if Wyoming ever approves an income tax, it would be in a time of crisis. Legislators, desperate for new revenues, might not consider the additional burden new taxes might impose on working people in the state.

“It would be slapped on as an overlay to the existing tax structure,” Smith said, explaining his intent. “It seemed to me people should get credit for what they already paid before they had to pay more. We tried to bring some equity into the tax structure, and the Legislature agreed with me.”

The ballot issue stated that the amendment “will provide taxpayers with protection against double taxation, providing a tax credit for any tax liability arising from a tax on income or in the event of passage of a state income tax.”

Voters, unsurprisingly, passed it with gusto.

With Smith’s tax amendment, most people would pay nothing extra …

How would this income tax scenario work under Smith’s Constitutional amendment?

Let’s say a person in Wyoming has $50,000 worth of taxable income, and the state sets an income tax rate at 6 percent. Without Smith’s constitutional provision, that would mean that this person would pay an additional $3,000 in state income taxes!

The prospect of that additional $3,000 is exactly why there’s so much opposition in Wyoming to an income tax. But, thanks to Smith’s amendment, this $50,000 earner would get to write off her sales and property tax, resulting in her likely paying nothing more than the does now.

According to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), middle-income people in Wyoming already pay an effective tax rate of 5.9 percent. So, for our $50,000 earner, that would mean she could write off $2,950, leaving her on the hook for a whopping 50 bucks to the state.

But, factoring in federal income tax, this $50,000 earner would pay no additional taxes overall—even if the state tax was slightly higher—since paying state income taxes gets you a credit toward your federal income tax payment.

… but Wyoming could raise hundreds of millions in revenue

While low- and middle-income Wyoming citizens might not fork over any extra under a state income tax, the state could raise serious revenues from its highest earners, who currently treat Wyoming like a Cayman Island tax haven.

The median income of Wyoming’s 1 percent is roughly $3 million, and the average effective tax rate for that income bracket is 1.2 percent. If that $3 million earner paid the same 6 percent state income tax as the $50,000 earner, and they got to deduct the 1.2 percent of taxes they already pays, they would still be on the hook for nearly $150,000 (a big number, we know, but they can afford it).

Estimating that Wyoming’s richest 1 percent tax bracket is comprised of about 2,000 households, their income tax alone in this scenario would raise around $300 million for the state—enough to cover three quarters of our current $400 million education budget shortfall.

Granted, these are rough figures. But the point is to give you an idea of how actually fair the Wyoming Constitution can be if we use it correctly, and how much we all stand to potentially gain with the implementation of an income tax.

The other thing an income tax would bring to Wyoming, of course, is economic stability—the lack of which prompted this whole conversation in the first place. Along with fairness, Wyoming’s spasmodic boom-and-bust cycle is also what motivated the TR2K committee’s recommendation:

“[With an income tax] state residents would assume a greater responsibility for the revenues the state receives and the resulting expenditures,” the final report stated. “Wyoming’s economic development efforts could experience more cohesiveness and certainty.”

A legacy of equity

Despite its innate fairness and other qualities, Smith said the inaccurate but common wisdom against implementing a state income tax will likely keep prevailing. He still thinks if Wyoming ever approves an income tax it will result from “an almost desperate situation.”

So does he foresee an income tax in Wyoming’s future?

“I think it’s unlikely but not absolutely impossible,” Smith said. He declined to give an opinion about whether a state income tax would be a good idea.

“I think things are so polarized right now that someone throwing an opinion from the outside wouldn’t really help anything,” he said. “[Legislators] need to take a good hard look at whatever decision they come up with.”

The former speaker said he is proud of his role in working to bring some equity to the tax system. And that wasn’t his only good deed in this vein. Smith also had a hand in establishing the state’s Permanent Mineral Trust Fund and creating a sales and use tax rebate for low-income and disabled folks, which were both important, innovative concepts.

But Smith says as he looks back at his legislative career, his tax credit amendment “is one of the things I helped put in place that can have some long-term value.”