Session recap: Criminal justice reform makes progress

Criminal justice reform was pushed out of the legislative spotlight this year by education funding, gun rights bills, and other issues seen as impacting more people—or generating more hype.

But the success of several positive criminal justice reform bills—aimed at reducing the number of state inmates, providing substance abuse treatment for addicted prisoners, and giving wrongfully convicted inmates a fair chance to prove their innocence—was one of the most important but under-reported stories of the 2018 budget session.

The topic received scant attention partly because comprehensive criminal justice reform bills have been brought forth and killed each of the past two years. Those bills were the results of long and intensive collaborative efforts, in which criminal justice reformers made sure to seek the input of a wide variety of stakeholders.

But the bills of years past died without even receiving a vote in both chambers of the Legislature. Why would anyone think the scattershot offerings this year would have a better chance?

A big part of the answer, it seems, is money. As the Legislature continued to stare down an estimated $900 million “structural deficit” during the 2018 budget session, lawmakers began looking more earnestly for ways to save. They noticed that Wyoming sure wastes a lot of loot locking people up.

The wide support with which several significant reform bills passed this year suggests that legislators might finally be willing to accept that commonsense, humane, money-saving criminal justice reforms are the best way forward for the state—even if it means softening the Legislature’s “tough on crime” stance.

Before reform, years of failure

To understand how dramatic the Legislature’s about-face was on criminal justice reform this year, we need only look to the miserable failure that reform advocates experienced in 2017.

When House Bill 94, a comprehensive criminal justice reform measure, landed on the desk of Senate President Eli Bebout (R-Riverton) in February 2017, it wasn’t a good bet to pass the Senate even though it had widespread support.

“If it’s a good idea, it will be back.” — Senate President Eli Bebout on killing criminal justice reform in 2017

HB-94 had already experienced two years of being drafted, stuck in committee, and heavily amended. Although it hit some stumbling blocks in the House last year, it was approved 31 – 26. Still, its main backers—judges, corrections officials, the state parole board, and good government groups—were nervous about its chances.

That’s because Bebout wasn’t a fan of the proposal. He didn’t like the $2 million price tag to implement HB-94, even though state officials estimated the bill would actually save $7.6 million annually and might even negate the need to build an expensive new prison.

While the parole board endorsed it overall, one board member who’s a friend of Bebout’s—former House Speaker Doug Chamberlain—privately told him he didn’t like it.

So instead of assigning the bill to a committee and risk having it come back to the full Senate for debate, Bebout simply stuck it in his desk until the deadline passed for assigning bills. It was never seen again.

He deservedly took a lot of heat for his action. He had ignored a chance to save a significant amount of money and listened to a friend instead of all the other stakeholders who strongly favored the bill. Bebout’s biggest transgression, though, was not allowing the whole Senate to consider whether the bill could do what its supporters claimed: reduce the prison population, provide substance abuse treatment for inmates with addictions, and help prepare prisoners to stay out of trouble on the outside.

Wyoming desperately needed solutions, but Bebout brushed all that aside. He told WyoFile, “A lot of effort was put in by a lot of people. But that’s the process. If it’s a good idea, it will be back.”

A measure to slow the prison “revolving door”

Several good ideas from last year’s bill did just that—they came back. And a few other criminal justice reform bills also won approval this year. Advocates did not get everything they wanted, but after the 2018 session, they seem to be on a roll.

The Joint Interim Judiciary Committee decided to break the omnibus reform bill that failed in 2017 into separate bills and introduce them individually. Perhaps the most important was House Bill 42, which provides judges non-prison sentencing options when they deal with people who violate probation or parole.

The idea is to insert several steps between rehabilitation and prison—and to convince people on probation and parole that they will be far better off obeying the rules than being shipped back to Rawlins.

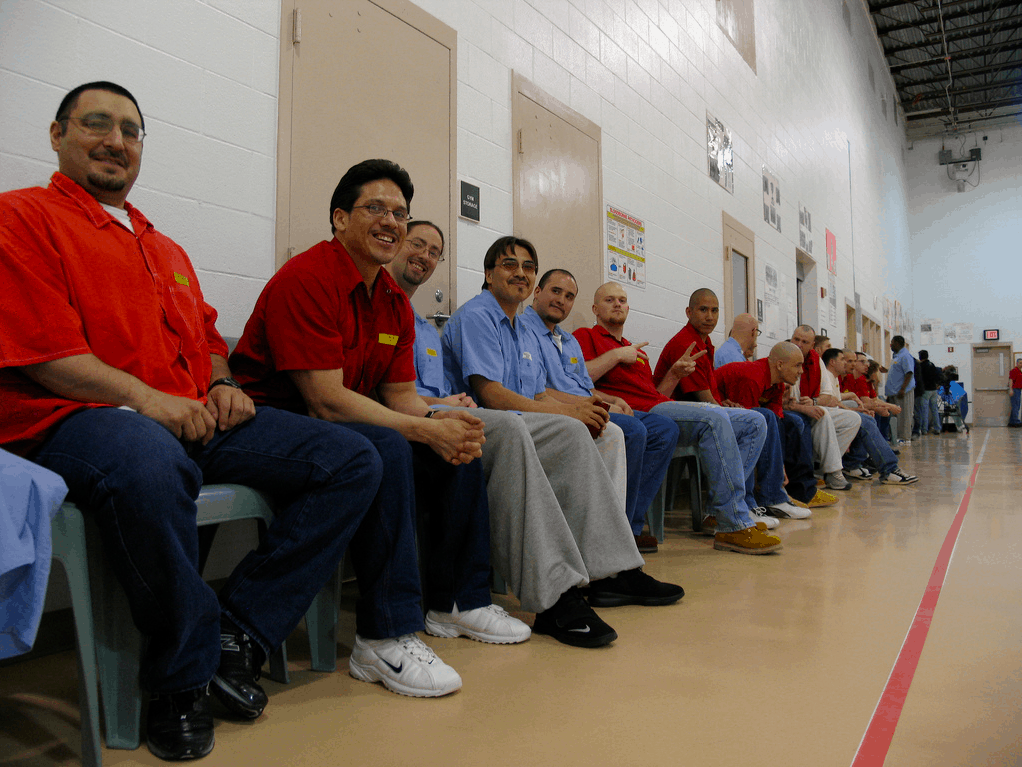

For many years, Wyoming judges have had essentially no choice when dealing with such violations other than to send folks to prison to finish their sentences or, if they were on probation, to serve suspended sentences. According to Department of Corrections officials, this policy has resulted in nearly half of Wyoming’s prison population consisting of people who have violated probation or parole. Meanwhile, the state’s overall prison incarceration rate has increased 300 percent since the late 1970s.

Under HB-42, probationers and parolees who have not committed a violent felony like murder, rape, or kidnapping can be placed in county jails initially for two or three days. Continued violations of probation and parole result in more jail time—up to 18 days, before the state places them back in prison. People who have committed several substance abuse violations can be placed in a 90-day jail-based treatment program.

The idea is to insert several steps between rehabilitation and prison—and to convince people on probation and parole that they will be far better off obeying the rules than being shipped back to Rawlins.

HB-42 also restores some funding for Department of Corrections substance abuse treatment. Last year, in a sweeping round of budget cuts, the Legislature eliminated all funding for DOC adult substance abuse treatment programs. HB-42 allocated nearly $600,000 for such treatment through June 30, 2020, when the program will be re-evaluated.

Only one legislator, Rep. Bob Nicholas (R-Cheyenne), voted against introduction of the bill. It sailed though the House 58 – 0, with two excused lawmakers. In the Senate, even Bebout voted for it, and HB-42 won unanimous approval, 30 – 0.

Now, the DOC will produce a report on how, specifically, the new policy will work, so it can be implemented in 2019.

An absurd law overturned at last

Another victory for the Judiciary Committee—and particularly for one of its members, Rep. Charles Pelkey (D-Laramie)—corrected an absurdly unfair provision in Wyoming’s laws.

For several years, Pelkey had sponsored unsuccessful bills aimed at changing state statutes that—get this—prohibited wrongfully convicted prisoners from using non-DNA evidence to obtain new trials if the evidence was discovered more than two years after their sentencing. (The two-year limit didn’t apply to DNA evidence.)

So, basically, up until just now, an innocent person in Wyoming be sentenced to life in prison, two and a half years could pass, new evidence could be discovered that someone else had committed the crime, and it wouldn’t matter—under Wyoming law, that person would have to stay in prison anyway.

“In spite of my 20-plus year friendship with Mr. Knepper, I had to keep from throttling him,” Pelkey said. “But he said he would join the effort to find a solution and he was true to his word.”

Chief Deputy Attorney General John Knepper single-handedly killed Pelkey’s bill in 2017 when he showed up at a Senate Judiciary Committee meeting and testified that he had serious concerns about the bill. He said inmates would waste judges’ time by filing frivolous petitions, and that the law isn’t necessary because, for instance, the governor can pardon innocent people.

In deference to Knepper, the committee tabled the bill, effectively killing it.

But the deputy AG said he would work with other stakeholders to improve the bill and bring it back. A committee that included Knepper and representatives of the Innocence Project, the DOC, the Wyoming Prosecutors Association, the Public Defenders’ Office, and the Wyoming Trial Lawyers met and, according to Pelkey, made it a better bill.

The Judiciary Committee took the reins from Pelkey this year by sponsoring House Bill 26, which effectively removes the two-year time limit on discovering new non-DNA evidence that proves a person’s innocence.

Rep. Charles Pelkey has been advocating to change Wyoming’s laws regarding exoneration evidence for years.

The House passed HB-26 by a vote of 58 – 2 and the Senate approved it 28 – 2. When it passed, Pelkey recalled how he had felt a year before when Knepper walked into Senate Judiciary’s meeting and stuck a dagger in the heart of his bill.

“In spite of my 20-plus year friendship with Mr. Knepper, I had to keep from throttling him,” Pelkey said. “But he said he would join the effort to find a solution and he was true to his word.”

Unfinished business

Not all bills that would have reformed criminal justice statutes, for better or worse, were approved in 2018.

Two bills Pelkey sponsored without the Judiciary Committee died. House Bill 189, to repeal Wyoming’s death penalty, failed to win introduction in the House. Meanwhile, House Bill 114, which would have made it easier for juveniles’ criminal records to be expunged, passed the House 54 – 4, but ran into trouble in the Senate Judiciary Committee, which defeated it 2-3. Senators Larry Hicks (R-Baggs), Leland Christensen (R-Alta), and Tara Nethercott (R-Cheyenne) are responsible for its defeat.

House Bill 55, which would have increased the amount of property damage necessary to be convicted of a felony, failed. So did House Bill 38, a Corporations Committee bill that would have increased penalties for misdemeanor unintentional voting violations and felony intentional voter fraud.

Not all changes were welcomed. Proposals to increase penalties for stalking and domestic strangulation passed this year—the latter has been a longtime goal of Pelkey’s. Anti-domestic-violence groups welcomed the changes. But they raised eyebrows among organizations concerned with the Legislature’s habit of passing new laws each year to imprison more people and increase prison-based penalties.

The Wyoming ACLU did not take an official stance on either of these domestic violence bills, but director Sabrina King pointed out in an op-ed that even well-intentioned laws like these contribute to Wyoming’s rapidly growing prison population, and likely do so without decreasing the incidence of domestic violence.

Piecemeal path to progress

While this year’s gains may not be the comprehensive reform many advocates have pushed for in the past, the Legislature showed that it prefers considering bills that allow them to make changes piece by piece instead of packages that try to incorporate several provisions all at once.

That multi-bill approach would logically seem to make the process longer and more uncertain, but the real-life result is that the Legislature embraced criminal justice reforms that it unceremoniously rejected in previous sessions.

The Judiciary Committee seems to have had an epiphany about how to get things done. If it means fewer inmates, addiction treatment that works, and cost savings, maybe state legislators will keep making better decisions instead of bowing to the interests of a few with questionable motives.